One of the highlights of OzSky was a visit to Siding Spring Observatory, the home of the Anglo-Australian Telescope, the UK Schmidt Telescope and the Uppsala Telescope, among others. As an amateur, it’s always interesting to visit these big professional observatories, see the big telescopes and something of the work that goes on there.

Siding Spring Observatory, located on the peak of Siding Spring Mountain – Mt. Woorut in the local Aboriginal language – is run by the Australian National University and was opened in 1964. There are a number of telescopes on the site, including the 3.9 metre Anglo-Australian Telescope, the 1.2 metre UK Schmidt Telescope, the ANU 2.3m Telescope, the ANU SkyMapper, the 0.5m Uppsala Telescope, and Faulkes South among others.

As a group, we were getting a behind-the-scenes visit to the AAT and, because of the large group, we were divided into two smaller groups. One group went to the AAT first, while the second group (the one I was in) went up the mountain to look at the other domes.

I took as many photos of the observatory telescope buildings as I could; the information I’ve added with each one is largely taken from the Australian National Observatory’s visitor information leaflet ‘The Telescopes of Siding Spring Observatory’, which is available in the visitor centre.

The Anglo-Australian Telescope dome. The AAT was opened by Prince Charles in 1974 and is a joint operation between the UK and Australia and run by the Australian National Observatory (AAO). One if its roles is to hunt for planets around other stars. It also did the Galaxy Red Shift Survey.

The ANU 2.3 metre is in the box-like building – the story is that the ANU wanted a new observatory building and were told they couldn’t have one but they could have a new office building instead. They built this ‘office block’ which houses the 2.3 metre telescope!

Faulkes South was designed and built in the UK. Run by the Los Cumbres Observatory Global Network, it’s a 2 metre Ritchey-Chrétien telescope which is used for research and education.

ANU SkyMapper. This is an automated telescope which is used for southern sky surveys, looking for trans Neptunian objects, supernovae, comets, NEOs and planets around other stars.

Solaris – built by the Polish Academy of Sciences, this 20″ Ritchey-Chrétien telescope uses photometry to look for planets around eclipsing binary stars.

UK Schmidt – operated by the AAO, this is a 1.2 metre survey telescope which has a wide field of view and is currently used to measure radial velocities of stars in our galaxy. Well known professional astronomer David Malin also used it to take detailed photos of southern sky objects.

Uppsala Telescope

One we’d walked back down to the visitors’ centre, it was time to go to the AAT dome. We were met by one of the staff, Chris, who gave us a guided tour. As with the ATCA visit, hard hats had to be worn (I did manage to avoid hitting my head this time!) inside the dome itself.

First, we saw the huge shipping crate the AAT’s mirror had been sent to Australia in. The 154″ mirror had been made by Grubb Parsons of Newcastle, England and shipped to Australia. Incidentally, the ‘Parsons’ of Grubb Parsons was Sir Charles Parsons, the inventor of the steam turbine engine which was used in many famous ships such as HMS Dreadnaught, Mauretania, Lusitania, Queen Mary, United States, etc. Turbines are still used today, although generally these are gas turbines used in some passenger ships and warships.

Inside the building we took the lifts up to the dome level and donned hard hats. First up was the control room; we didn’t know if we could get in there but the duty astronomer was happy for us to take a look.

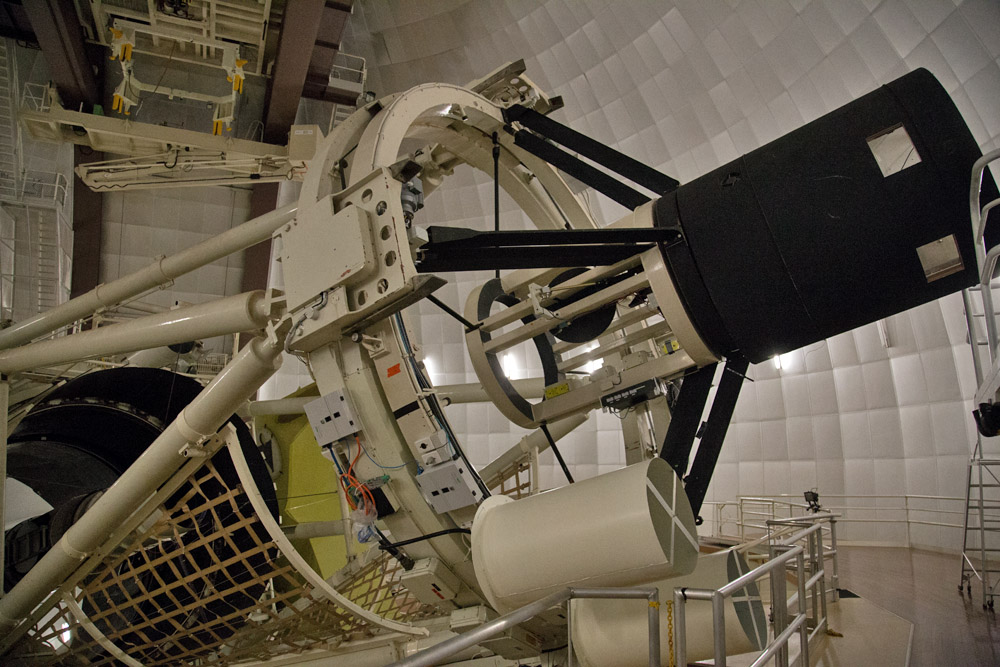

From there, we went into the dome itself to look at the AAT.

The photo below shows a model of the AAT with the real thing behind it.

The back of the telescope and the horseshoe mount. The AAT had been lowered because it was in maintenance mode and the needed to do some work on the top end; luckily for us it meant they needed to move it while we were there.

The video shows the telescope and dome being moved, it starts off slightly out of focus but does sharpen up. As with the still photos I used my Canon 6D and 24-105mm lens but even with a full-frame camera I couldn’t fit it all in, even at the 24mm end.

The top end and upper cage.

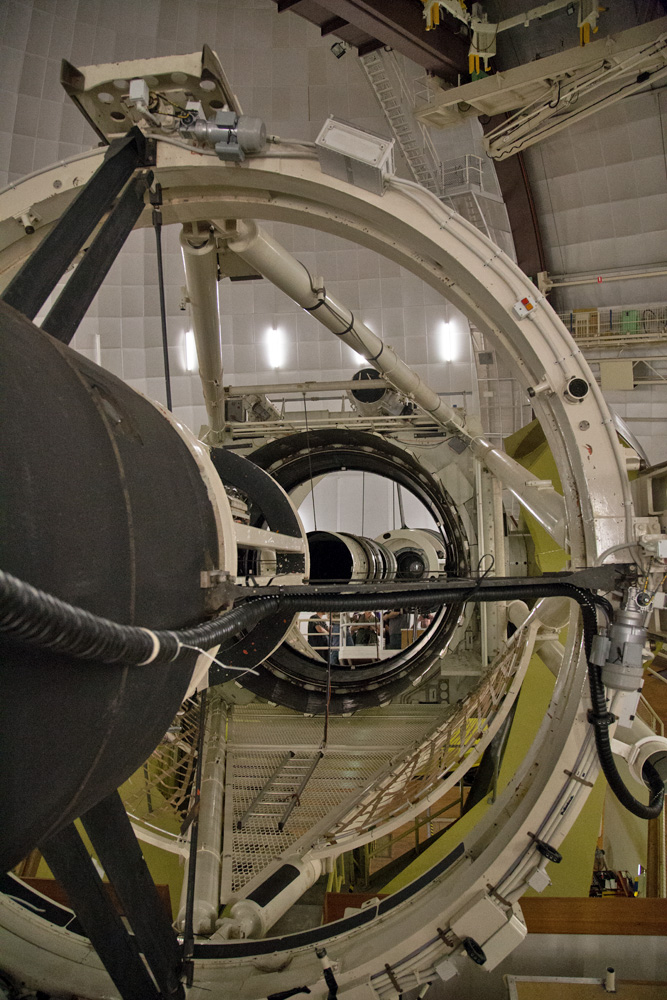

Looking down the business end into the primary mirror. Attempts at selfies – which we all tried – weren’t that successful as it’s actually quite hard to get yourself in the mirror and take a photo!

We went outside on to the dome catwalk. The view from there was fabulous, very scenic. It is, however, not for those with a fear of heights – you are, of course, perfectly safe but it is a long way down.

The view from the top is fabulous with vistas across the Warrumbungles and beyond, as far as the eye could see. The evidence of the fires in January 2013 was plain to see, with blackened trees everywhere. The fire had come very close to destroying the observatory – it came right up to the AAT’s dome at one point – and they were very fortunate that there was little damage to the observatory itself, although the astronomers’ lodge was burned down and one astronomer, Rob McNaught, lost his house. One of the support staff at the AAT told us of how he escaped the fire; he had a very narrow escape because he took his motorbike, leaving his car on the mountain (his car survived), but by the time he realised he should have taken the car it was too late to turn back. As he said, he was very lucky.

The area is beginning to regenerate but there are some trees which won’t recover, simply because they are either too young and small or because they are on the upper slopes where the heat was more intense. Wildlife died, with the local koala population all but wiped out and kangaroos and emus decimated; domestic animals died and people lost homes. All this because of a couple of moron campers in the nearby Wambelong area who started a camp fire despite all the warning signs and being told not to.

In the first photo below, I think the green bit at centre is the Wambelong camping area where the disaster began.

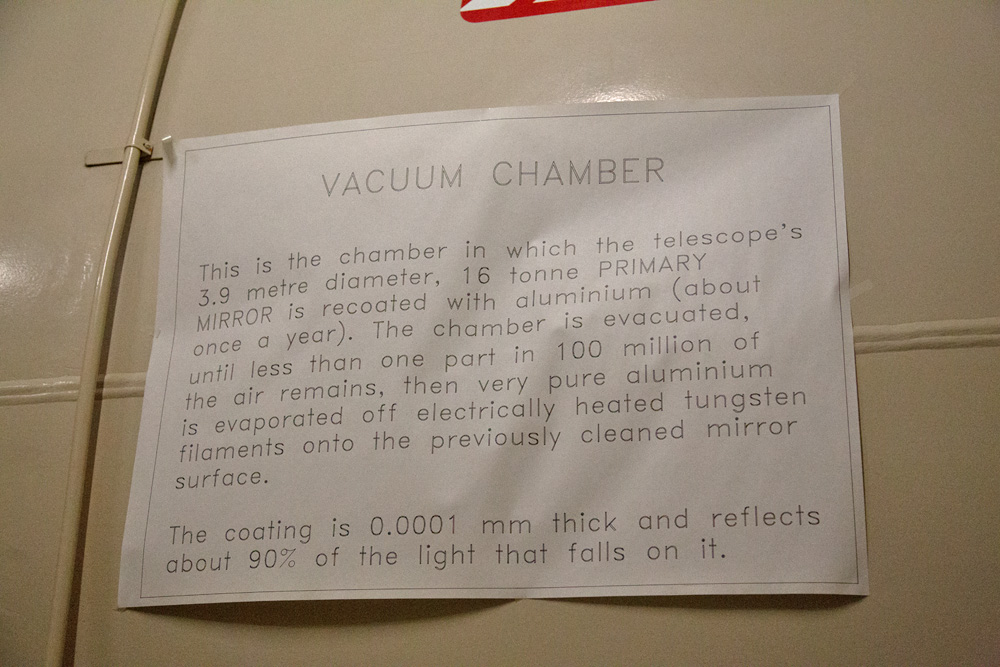

We walked right round the outside of the dome before returning inside. From there we went down to the aluminising room where, once a year, the AAT primary mirror is recoated with a fresh layer of aluminium. As our guide said, if the mirror had to be removed for cleaning once a year, it may as well be recoated instead.

We walked right round the outside of the dome before returning inside. From there we went down to the aluminising room where, once a year, the AAT primary mirror is recoated with a fresh layer of aluminium. As our guide said, if the mirror had to be removed for cleaning once a year, it may as well be recoated instead.

The 16 tonne mirror is removed from the telescope and lowered through a trap door down into the vacuum chamber, which is a task that has to be done with great care; if the mirror was damaged in any way, that would mean the end of the AAT’s life which would be tragic indeed.

That was the end of the visit, which was very interesting. I’d always wanted to visit Siding Spring, which I didn’t do last time I was in the area, but the OzSky group got a great behind the scenes look at how one of the world’s biggest observatories operates. For me the highlight was watching the dome and the AAT moving, which wasn’t done to show off to visitors but just great timing on our part, showing up when they were moving the equipment to work on it.

Thanks to Donna Burton and her husband Chris (our guide) and the OzSky organisers as well as the staff at the AAT.